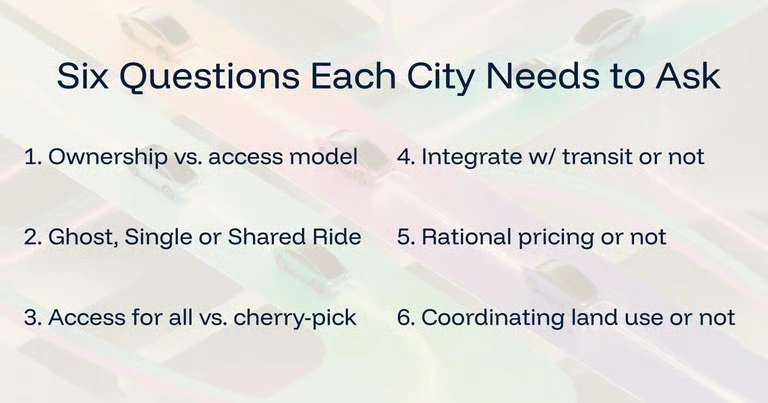

Ownership model or access model? ⬅️ today’s focus

Single-occupancy or ride sharing? ⬅️ today’s focus

Integrate with public transit or not?

Rational pricing structure or not?

Coordinated with land-use planning or not?

Access for all vs. cherry-pick market?

In the ownership model, AVs replace human drivers but privately owned vehicles still dominate the mobility system.

The access model envisions fleet-based AV deployment—such as Waymo and Luobo Kuaipao (Apollo Go). At scale, this model could drastically alter the optimal number of vehicles needed in cities, in theory.

But optimal is far from realized. Empirically, ride-hailing has not reduced car ownership in the U.S.—see our study, “Impacts of Transportation Network Companies on Urban Mobility” (link).

Fleet size needs to be managed to avoid two extremes: operators tighten supply and push up prices; or flood cities with too many cars to grab market share, worsening congestion.

To manage this, cities and industry need to negotiate the optimal number of AVs. There is a short-term optimal: given the existing private cars, dynamically cap fleet size according to ridership needs; and a long term optimal, when households adjust their car ownership—if service levels and prices become sufficiently attractive to shift away from owning cars.

Carmakers, Mobility Providers and Cities

Carmakers favor the ownership model, preserving unit sales and margins.

Mobility Service Providers (MSPs) prefer fleets to amortize high fixed costs (e.g., sensors, software). MSPs may partner with OEMs to design fleet-specific AVs: 24/7-capable, easy to clean and maintain.

Cities may support fleets to achieve system-wide goals: congestion management, equitable access, and operational efficiency.

Parking vs Stopping

AVs redefine the concept of parking. It will split into two functions:

Stopping for pickups/drop-offs (curb access becomes key)

Storage during vehicle maintenance, cleaning, charging and storage

Plausible pathway:

Fleet-first, ownership-later. Cities have a window to set norms by licensing fleets, allocating curb space, and aligning road user fees.

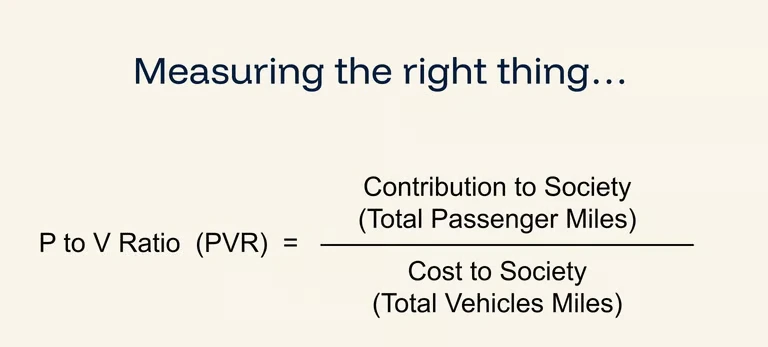

First, Define Passenger to Vehicle Ratio (PVR), simply

Passenger miles are the benefit to society; and vehicle miles are the cost to society.

PVR measures the overall efficiency of the mobility system. There are many notions of efficiency. PVR captures one of them.

Second, Measure PVR

Basic stats in the US:

PVR for private light-duty vehicles: 1.5-1.7

PVR for UBER/Lyft (excluding driver mileage): 0.45-0.65

AVs could make it worse—picture this: in downtown Manhattan, parking costs $25 for 30 minutes, and running an AV costs pennies. What will AVs do? They’ll circulate the blocks—empty.

All mobility providers should report PVR regularly.

Third, Increase PVR

Reducing congestion requires increasing PVR. Three ways to do so

Cut the ghost miles

Reduce deadheading with better algorithms for matching and routing.

More importantly, empty AVs cruising dense downtown need to pay their fair share.

Increase ride sharing

UberPool and LyftLine both tried and failed.

They could not find a price low enough to attract riders and high enough to make money.

Sharing penalty” is too high.

COVID-19 became the perfect excuse to stop trying.

Support Public transit

It remains the ultimate ride sharing mode—with the highest PVR.

Physics vs. Psychology

Pooling rides isn’t just a technical puzzle. It’s a social one.

The physics we’ve mastered:

When two trips have close time windows, and their origins and destinations are nearby, we can pool them.

It is a complex but well-defined mathematical problem. And we know how to solve it.

In fact, the same algorithms used to pool people (ride-sharing) are used to pool packages (food delivery).

The brilliance of mathematics: Once solved, it applies universally.

But treating boxes and people the same way? Clearly, something’s missing.

The psychology is harder:

Sharing a ride with a stranger is much more than travel time and travel cost—it is a social endeavor.

People aren’t packages. They have preferences, fears, and biases.

Some enjoy the encounter while others feel uncomfortable.

Like any public or semi-public space, when people interact, amazing things happen—and ugly things happen too (safety concerns, social prejudices, etc.).

And let’s face it: Americans don’t like to share rides.

The rosy view:

Pair an entrepreneur with an angel investor,

An art historian with a science fiction writer,

An electrician with a home buyer…

Or, may I dare? A Republican and a Democrat in the same ride.

➡ See “Mobility sharing as a preference matching problem” (full paper)

Carpooling can be optimized to promote social integration across diverse groups—extending its benefits beyond just efficiency and environment.

➡ See “Carpooling for social mixing” (full paper)

The realistic view:

The fear of negative interactions outweighs the hope for positive ones.

➡ See “To Share or Not To Share: Investigating the Social Aspects of Dynamic Ridesharing” (full paper)

While utilitarian factors (cost, convenience, availability) drive initial adoption, discriminatory attitudes remain an obstacle to long-term engagement with shared mobility.

➡ See “Rider-to-rider discriminatory attitudes and ridesharing behavior” (full paper)

What do you think? Will AVs change the psychology of sharing? Or just automate the loneliness?

More in the next article.

join my newsletter to understand what actually works, what’s not, and what might come next