The formal part of “doing science” is taught in meticulous detail, yet the first step, generating initial ideas, remains mysterious.

“Coming up an idea for research” feels ad hoc, idiosyncratic, inaccessible, even not teachable.

Naturally students feel difficult to start, “when is my Eureka moment?”

Science is asymmetrical: between how ideas are born and how they are confirmed

(See more at Ludwig and Mullainathan 2024)

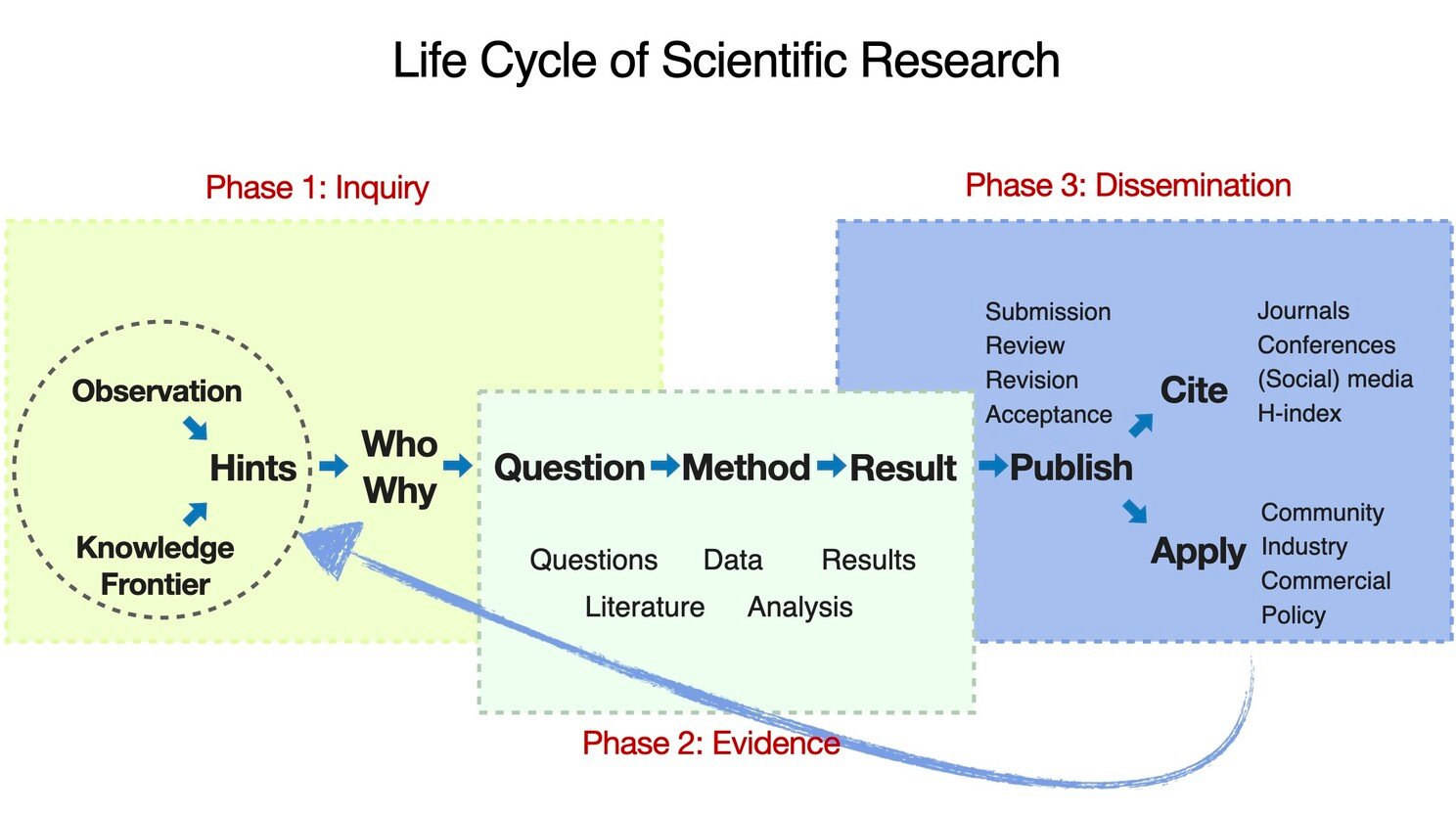

Scientific research has three phases:

Phase 1: Inquiry (Hypothesis Generation)

The informal, creative prequel to formal science.

New ideas originate in an unstructured process, observation, intuition, inspiration, and imagination.

Phase 2: Evidence (Hypothesis Testing)

The well-structured, formal part of science.

Ideas are meticulously tested using data, statistics, and formal models.

This part is recognized as “doing science.”

Phase 3: Dissemination

Where new knowledge is shared and applied.

Publication, citation, and application ensure that new knowledge contributes to the frontier and inspires the next generation of inquiry.

Applications can include new technology, commercial products, community programs, or public policy.

Of course the three phases feed back on each other and we iterate.

The idea generation phase: why it feels unteachable

Phase 2 follows precise, codifiable protocols.

Phase 1 resists formalism and relies on singular burst of inspiration.

Phase 1 is human and idiosyncratic.

Phase 1 is the most creative, the most fun part of doing science.

But it is also the source of many students’ frustration!

Because it feels just mysterious, unteachable.

Waiting for one’s Eureka moment is depressing.

Worse, in scientific publications, authors only report Phase 2, but not Phase 1!

We do not know how to write rigorously how our ideas are conceived so we do NOT do it.

Since we do not share it, we do not learn from each other.

The current system lacks the mechanism to share our Phase 1 thinking. As a result, many students find it difficult to begin, believing that it is unteachable.

[Exceptions are philosophy of science, history of science, and biographies.

- Karl Popper’s critical rationalism, Thomas Kuhn’s paradigm shifts, Imre Lakatos’s research programs, or Paul Feyerabend’s epistemological anarchism. Too abstract!

- Historians study social context, personal experience, technological conditions, accidental triggers, serendipity, … which made the scientific ideas possible. Or scientists themselves reflect their own experience, only 30 years later in their biographies. Too late!]

Call for action: Every paper should have an appendix “where my idea came from”

It is informal, no need to be rigorous or evidenced.

It does not even need to be logical or rational.

It can be a metaphor, an analogy, an anecdote, whimsical, …just somehow two neurons touched each other.

It is impossible to formalize intuition and creativity.

But write something: whatever the trigger was.

So that we can inspire each other.

An Attempt at a Quasi-Structure

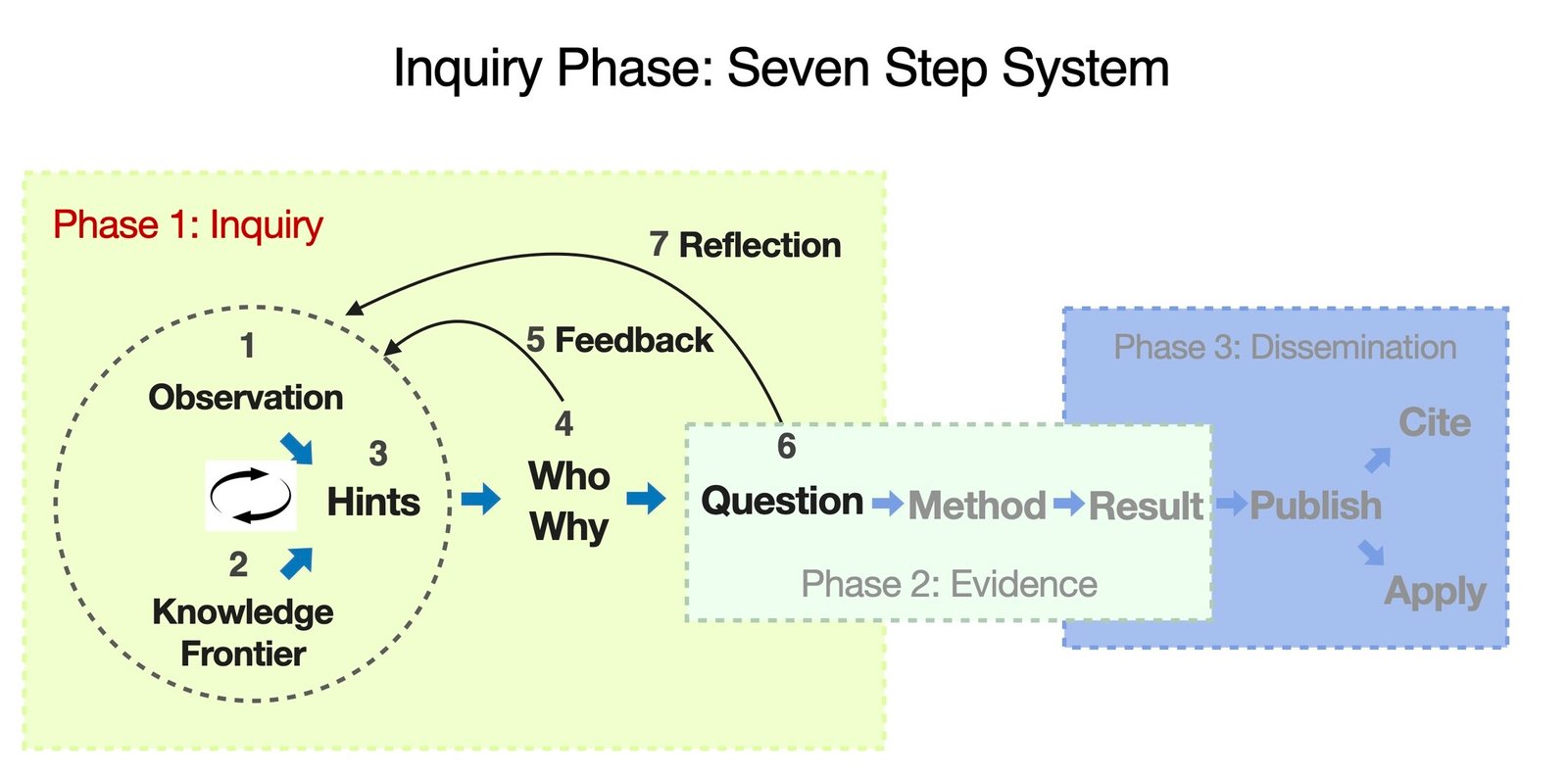

To provide a moderate level of structure and demystify the Inquiry Phase, I am developing a SIM system for research question creation.

The SIM system addresses two questions: “Where do research ideas come from?” (The Origin) and “Who does this research help?” (The Purpose).

It aims to:

- Provide a method: change the elusive process into a manageable quasi-structured journey

- Form a habit: constantly observing, reading, and developing hypotheses. Regularly asked “why?” and train the thinking muscle.

- Ensure intellectual ownership (“this is my idea”) and a sense of purpose (“someone’s life could be better because of this research”), and therefore intrinsic motivation.

The system is organized into seven steps.

Step 1: Seeing the world like a scientist

Research begins with observation.

Identify and describe a natural phenomenon or human behavior that sparks your interest.

Do not taking things for granted and ask “why?”

Be comfortable to propose naïve, intuitive theories.

Form a habit of doing it all the time.

Step 2: Frontier of Human Knowledge–Model the Best

A personal observation alone is insufficient.

One must understand what is already known to make a contribution.

Immerse oneself in the frontier of human knowledge.

Read top academic journals and scientific literature.

Model the best.

Step 3: Weak connections: between your observation and knowledge frontier

Appreciate connections, especially weak, distant, or surprising ones, between your observations and knowledge frontier.

When are ideas born?

- neurologically it happens when neurons connect

- biologically it happens when genomes remix

- sociologically it happens when people interact

Ideas are born when they kiss each other.

Step 4: Care for the “Who” and “Why”

A research idea gains purpose when connected to people.

Identify who your research could help.

Interview them to understand their needs and perspectives

Shifting focus from “focusing on oneself” to “focusing on others”.

Step 5: Feedback Loop

Use insights gathered from step 4 to sharpen your focus, or pivot your idea.

Purpose defines importance.

Step 6: Define the “What”

Deconstruct your rough idea into components: subject/object, variables, relationship and action, and setting. Challenge each of them.

Reconstruct and formalize it into a structured, specific, and testable research question.

Conduct a targeted literature review: step 2 scans and step 6 focuses.

Evaluate the question against the C.R.I.S.P. criteria: Clear, Relevant, Innovative, Specific, Practical.

Step 7: Reflection and Integration

Look back at the full circle: how your initial spark evolved into a formal question.

Reflect on your toughest challenges and valuable skills developed.

Integrate all your work into a research proposal.

I’m writing each of the seven steps here and will teach them in Scientific Inquiry Mastery